To prepare or not to prepare, that is the question”

– Case Interview Hamlet

Back when I was a candidate I constantly feared I was preparing too much.

What a strange thing to fear, isn’t it?

I had never felt something like that before. I had never feared studying too much for a test, or practicing too much of a skill, or eating too healthy.

Sure too much of a good thing can be bad… Some people die of drinking too much water. But I certainly wasn’t getting intoxicated of case interviews by studying just a couple hours per day.

And yet, it was a fear that was backed up by the opinions of countless “experts” on the field.

I’d hear about being careful not to be too prepared from case interview gurus and experient managers from top consulting firms alike.

They’d say I had to prepare, but too much of it would actually hurt my chances of getting an offer. The argument would go something along the lines of:

Do read a couple of books and practice up to 10 or 20 cases, but beware not to obsess too much about it or do too many cases. Practicing too much will make you sound like a robot and limit your creativity in a real case. You will begin to force fit frameworks into problems that need an original solution and then fail. It is probably best to practice a little but then leave some room to your own talents and creativity on interview day.”

I have to say it, it was pretty hard to deal with this fear of preparing too much. The case interviews were quite a big deal to me – working at a top consulting firm was a professional dream. And I was not used to dealing with being ill-prepared for situations that were big deals to me.

Maybe because I honestly wanted to be at my best at D-Day, the overpreparation argument never really clicked.

I mean, imagine a musician getting the following advice before an important recital:

Do understand a bit of the theory and practice a song up to 10 or 20 times, but beware not to obsess too much about it or play too much. Too much practice will make you sound like a robot and limit your creativity when playing it for real. You will begin to force fit musical scales into songs that need an original composition. It is probably best to practice a little but then leave some room to your own talents on recital day.”

Bullshit, right?

I mean, surely you don’t want to sound like a robot. Nor would you want to force fit things into situations they don’t fit. And no one wants to limit talent. But still, why would practicing more cause those things to happen?

Okay, I know what you’re thinking. Music does not apply. Because you know exactly what you’ll be playing, you can practice to perfection. Case interviews, on the other hand, require improvisation skills for you can’t know what kind or problem you’ll get. Well, there’s another field that has certain rules and principles, a lot of improvisation required and high stakes all-or-nothing moments: martial arts (along with many competitive sports).

Now imagine a martial arts coach saying:

Do know your moves and practice 10 or 20 fights, but beware not to obsess too much about it or practice too much. This will make you move like a robot and limit your creativity when fighting for real. You will begin to force fit your moves into a match that requires new combinations of kicks and punches. It is probably best to practice a little but then leave some room to your own talents on fighting day.”

Not only would this guy get fired, his client would be lucky if he didn’t end up in a hospital.

And I’m not cherry-picking examples here. Every craft requires tons of deliberate practice. I don’t know how many hours, some say it’s 10,000. No matter what type, overperformers always practice more than underperformers. The right kind of practice at least.

I challenge you to find a skill that is better done with little practice.

If that’s true, why are case interviews so special in the sense that preparation hurts? Is solving business problems in a structured way such a bizarre skill that practicing just one or two hours per day might be harmful to your performance?

Or could it be that these “experts” don’t know jack of what they’re talking about?

How to give a speech at TED (and how this is similar to your case interview prep)

Most people would rank giving a TED talk in the original conference a pretty high-stakes event in their lives. You’re showing your life’s work to the world. Plus, almost everyone is terrified of public speaking.

For me, the most incredible thing about TED is that everyone speaks so damn well. It seems they’re all natural public speakers. But could that be the case? They’re such a diverse group of top scientists, activists, public servants, technologists etc. It’s unlikely that all top people in their field are also great at public speaking.

Well, it turns out TED has a team that teaches these speakers how to prepare for their speech. And because it’s a high stakes moment in their careers, they prepare for months.

One of my favorite bloggers has written a hilarious description of how it is to prepare to one of those. Here are a couple things he had to say about how to give a flawless TED talk:

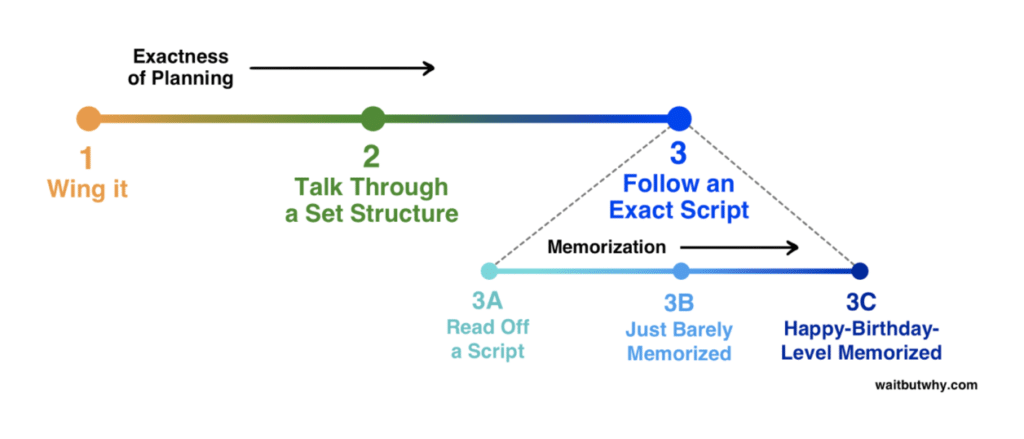

He says there are three methods to do a speech: to wing it, to talk through a set structure and to follow an exact script. He also says that the last method has nuances based on how much you’ve memorized the script. The methods to the right are better planned but also take more preparation work.

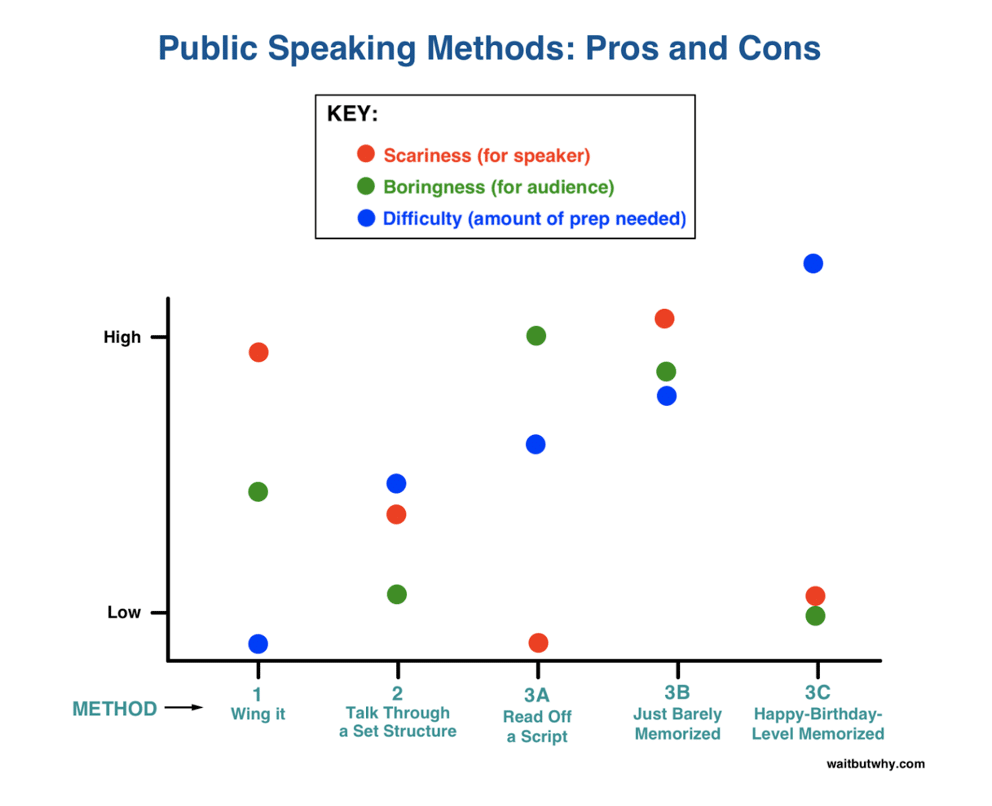

Now, the interesting thing is in this second chart: there are two methods that are better than the others when giving an important speech. If the speech is important but not life-changing (such as a university presentation or a weekly meeting with your boss), you should talk through a set structure.

However, to give the best speech possible (the kind you expect from a TED talk) you need to have the deepest level of memorization possible. That’s method 3C, the realm of subconscious memory (the kind of effortless recall you have when singing the “Happy Birthday” song).

If you are to read a script or barely memorize the speech, it is better to just talk through a structure as you will sound more natural.

But if you memorize the speech at a root level, you will sound natural. That’s what actors do – they’ve memorized it so deep that they’re not making effort to recall.

What this means is that, to give a speech, it is better to either prepare A LOT or very little (just to have a structure to talk). Roughly memorizing is worse than doing less work and talking through a basic structure.

But rough memorization is a necessary step if your goal is to reach the kind of subconscious memorization all TED speakers achieve before their talks.

Here’s what Tim Urban (the blogger) has to say about Level 3C preparation:

When the stakes are high and you want to deliver your best talk—but you’re not a seasoned pro who can pull off Method 2—you’re left with only one option: 3C. You have to write a great script and memorize it cold. 3C gives everyone an option of basically ensuring that you give a great talk, with relatively low risk. You only have to do one thing: spend eternity prepping. 3C takes forever. Writing a great script means working on it a ton and carefully honing every sentence, and memorizing it to Happy Birthday level takes a huge amount more time. You’re essentially writing a play, casting yourself, and then learning the part well enough to act it on a stage with no fear of forgetting your lines. Preparing to this level is a nightmare—but if the stakes are high enough, it’s worth the time.”

So, high stakes make it worth to prepare a lot. Hmm, I wonder if there’s something here for those going through case interviews…

“Hey Bruno, but this is all about giving memorized speeches. Case interviewing is not that, it is the applied skill of solving business problems. You can’t memorize any of it. What does one have to do with the other?”

Great question! I think this is somewhat related to the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

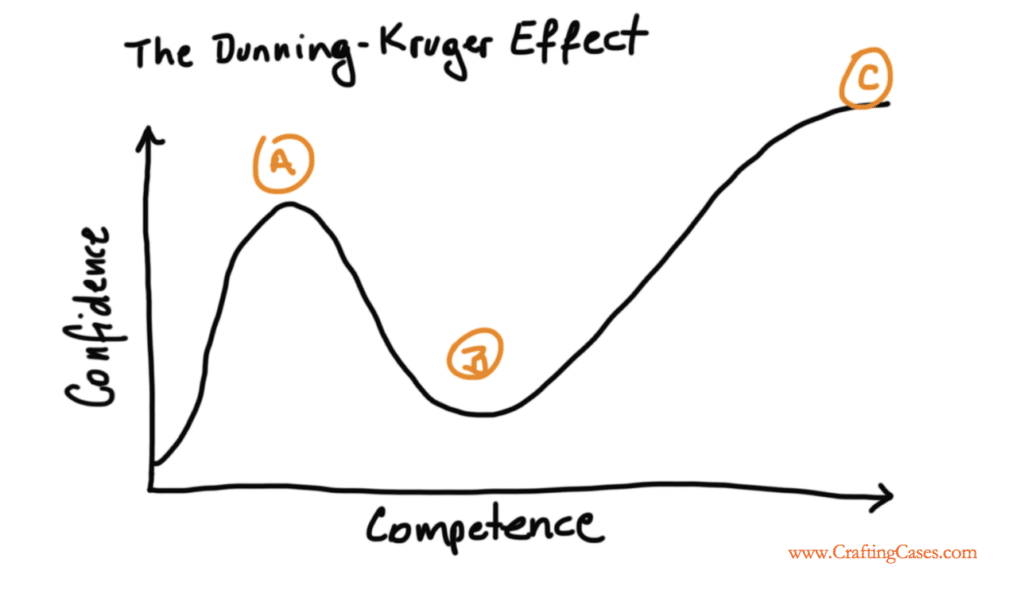

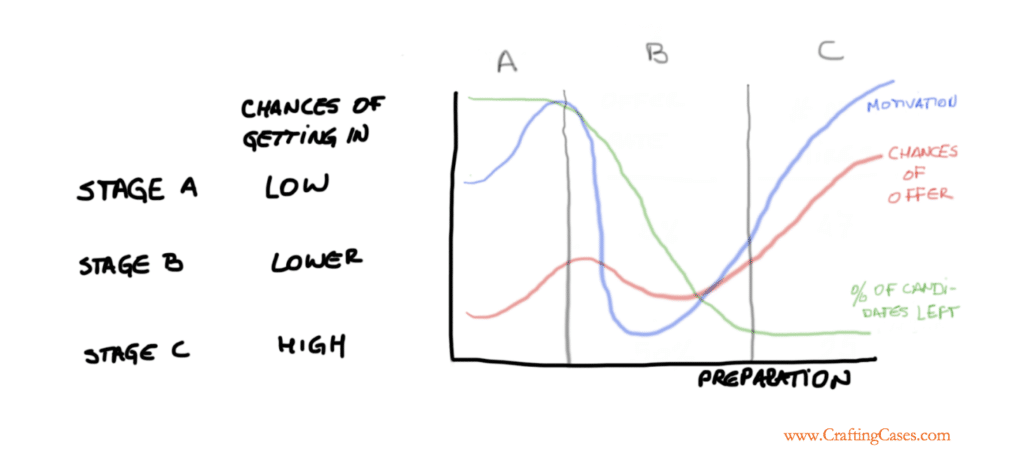

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a well-known cognitive bias that shows that people who know a little about a subject have almost as much confidence as experts in the field (Point A on the graph).

Of course, as they dig just a little deeper they realize there are many things they don’t know and freak out! Their confidence plummets (Point B). It will take them a fair amount of extra competence to get the confidence they once had back (Point C).

Every single competent candidate I’ve met has gone through these stages.

They’ve all been at Point A, where they felt like wizard business advisors that could turn whole companies around using nothing but “Revenues – Costs”. (That’s usually after reading a case interview book and doing a few cases with friends).

They will then do more cases and fail some of them. Their confidence will quickly drop and they will feel like they’re never gonna really learn this. They start getting cynical with learning this and believe “some people are just born with it”. They’ve reached a plateau, and feel it’s the limit of their talents. Those are the feelings at Point B. It’s a truly miserable place to be in.

Some candidates will persist and keep pushing their improvement. If they combine persistence with the right methods, they will get to Point C. Here’s where the magic happens. You get confident again, but it’s not empty confidence as it was in Point A. It’s confidence that comes from competence. Solving cases becomes easy. There is absolutely no fear that you won’t be able to solve a case, as you don’t fear riding a bike. You once feared to ride bikes, but now it’s just something you do.

The same happens with structuring and solving business cases.

I’ve seen that happen to myself and with several clients. Many have told me the real cases at consulting firms were much harder than the ones they’ve done when practicing, and yet were easy. They were so competent nothing would stop them.

Don’t be Jon Snow

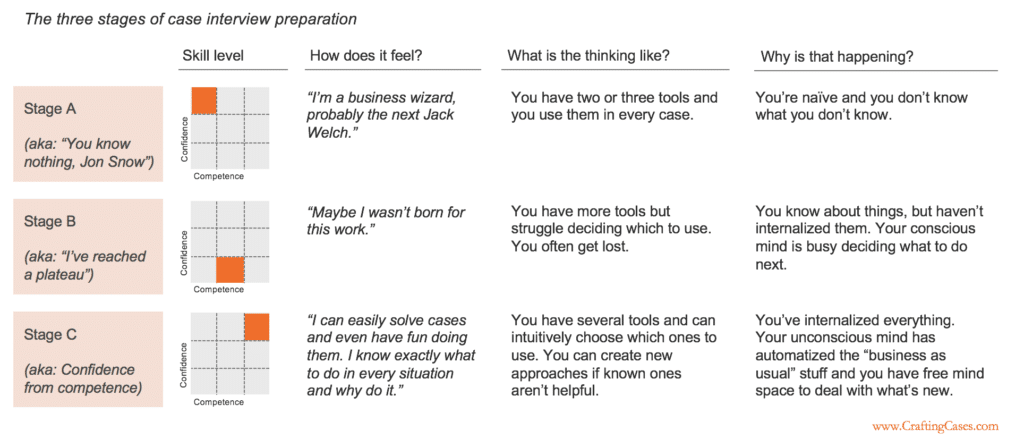

The chart above summarizes the three stages. Take a look at it and try to find in which stage are you in. But beware: the naivety of stage A implies you will think you’re on stage C. Their confidence stems from the fact that they’re unaware they don’t know their stuff.

A few indicators you’re on Stage A, and not Stage C are: (i) you’ve done less than 20 cases, (ii) you can’t create your own structures from scratch, (iii) you use the same structures for every case, (iv) you get lost if the case is not on a for-profit business, (v) you’ve read more than you practiced.

Why does the overpreparation myth exist?

By now you’re probably thinking: “okay Bruno, that makes sense. But why should I trust you and not the other 99% of people who say I should be wary of preparing too much? They can’t be all wrong…”

Well, one way to look at the question is: if this myth was wrong, why would it persist?

I think there are four possible reasons for that.

1. Everyone’s just repeating one another

One possible reason this myth persists is that everyone’s just repeating one another without really thinking about it. People say over preparation is a thing because someone has said to them in the past and they didn’t really spend time thinking about it. They’re just passing it forward without thinking too much about the consequences.

Given how many unhelpful things are repeated to exhaustion in the world of case interview preparation, I think there is a fair chance that this is what’s going on. Just think how many “experts” are out there telling you to read a certain “case interview bible” from a famous professor even though everyone knows the book merely scratches the surface and has little if any actionable advice.

2. The correlation = causation fallacy

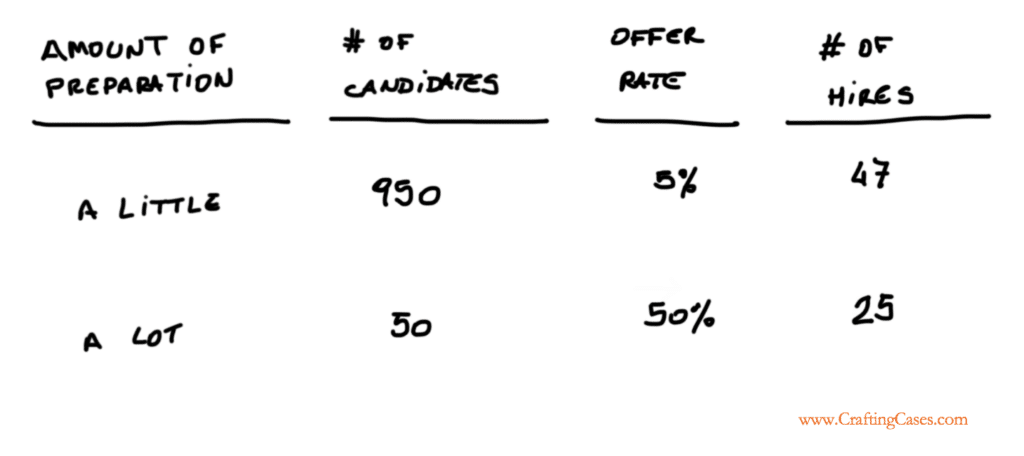

Another reason may be that they’re looking around and seeing that most people who get into MBB did not do 150 cases. And most people who do practice a lot end up not getting offers. That should mean that too much preparation hurts, right? Well, not quite…

In a scenario that only 1 in 20 people have prepared extensively and they have a 10X higher chance of getting in, most of a firm’s consultants will be those who’ve practiced little. So if you look at your friends and most of those who got offers didn’t prepare a lot, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t.

I refuse to believe this is the main reason why some consultants advise candidates not to prepare extensively. Consultants are mostly rational creatures. But this may reinforce their idea that it’s perfectly okay to study just a little.

Especially if they’re part of the majority who did get offers by doing just 10 or 20 cases.

They will think that because it worked for them, it is the way to go.

3. They’re trying to protect you

Being at preparation stage B (the point where your confidence plummets) sucks!

You feel like you’re never gonna get there. Like you’ve reached your max and it’s not enough. Some people even feel they’ve unlearned. It’s frustrating.

There’s reason to believe it doesn’t help you on your interviews, either. I mean, at stage A at least you’re confident.

Sure it’s empty confidence, but if you’re lucky enough to get simple cases and happen to naturally think and speak like a consultant you might get your offer.

(How do you know if you’re a natural? Simple. If you have thought in a structured way your entire life and your go-to way to approach mundane problems is to use frameworks and categorize things, you might be it. If creating structures from scratch doesn’t come easy, you are not. If you’re not, don’t worry: the vast majority of consultants at McKinsey are not naturals. Even the best partners have learned the craft the hard way.)

Stage B might be the most dangerous of all.

You’ve dropped your plans of just learning a couple of frameworks and going with the flow. But you also can’t ace every case yet. You know a little more than the stage A folks, but have lost the naive confidence they have.

Stage B is that point where you drop the script and memorize the speech by heart, but don’t have it well memorized yet.

It’s when you’re learning to ride a bike and drop the training wheels.

Training wheels are comfortable, and falling sucks. An overprotective parent might not want to have their child drop their wheels because they don’t want to see their child get hurt.

An advisor trying to protect you might say “don’t practice too much”. Stage B hurts.

A complicating factor is that because stage B sucks so much, most people stop preparing before they ever reach the promised land of stage C, where every case is easy.

That means they’ve gone through a lot of trouble and didn’t get the benefits. People who don’t like to see you suffer don’t like to see you put in a lot of effort to have your chances of getting the offer declining.

Just like when preparing to give a TED talk, if you’re not to go all-in on your preparation, if you’re not to reach stage C, it is better to just stay at stage A.

But remember why all TED talks are amazing? Because it’s a high stakes moment in your life, and people want to give their best shot at things like that.

If a consulting interview is a high stakes moment for you, why not give it the best shot possible?

I get it why people try to protect you by telling you not to prepare too much. Stage B is the longest, most painful AND you may have even fewer chances of getting in than the guy who doesn’t know enough and either gets away with the standard frameworks or actually has to think during the interview.

But I don’t agree with those people.

I don’t think the advice you should get is to prepare just a little bit and pray that the thinking habits you learned as a child are the right ones for consulting. What I wish someone told me when I was preparing was that if I stuck to shortcuts and magic bullets I’d be doomed but that if I chose to learn the right way, it was actually possible to do so.

But hold on, there’s a fourth possible reason this myth exists.

4. Preparation (as it is) is indeed harmful

It could be that too much preparation is indeed harmful to most candidates. That would mean that stage C doesn’t really exists, or is unattainable.

I think it’s within this hypothesis that concerns of a candidate limiting their creativity, or sounding like a robot, or force-fitting frameworks arise.

But it’s weird that more preparation creates a less natural, less creative candidate, isn’t it?

It’s like saying that if you solve too many problems you will hinder your ability to solve new ones. Or like saying that a musician that learns too many songs will have a lesser ability to create new ones.

Let’s get the musician’s example to understand what’s going on. Suppose there are two musicians: one who has learned to play 10-20 songs and another who has learned 300 of them. Who’s gonna create better music? The first or the second?

It depends!

The second probably has an advantage, as long as he actually learned music. By that I mean he understands each of the 300 songs he learned. He knows why certain notes follow a pattern. He has learned the inherent techniques within each song and why they’re there.

If, however, he just memorized them and has no clue why things are the way they are and what’s going on, he has no real advantage.

Now suppose the 300 songs the second guy has learned are all within the same musical framework – similar scales, rhythms and patterns. Anything this person creates will be limited to what he has learned.

Now the 10 songs guy might have an advantage.

Julio had a teacher who used to say that practice makes permanent. A nice spin on the “practice makes perfect” motto.

The more you practice, the stronger your mental pathways to do that thing become. That means you should be very careful with what you practice.

If it’s quality practice, you’re on a path of reinforcing thinking patterns that will help you out in the future. If it’s poor practice, however, you’re just making bad habits stronger.

From experience I know more than 90% of candidates out there are practicing poorly.

They’re practicing similar cases, with people who have no clue what’s going on and why things are the way they are. They might know their mistakes but they don’t really know how to fix them, so they keep doing them.

They’re making bad habits permanent.

(This is good news for you, as you can easily outcompete these people in quality of preparation.)

You will only get as good as your teachers and materials are.

It’s pointless to try to learn something from a book full of mistakes or that doesn’t take you to the level of detail you need to really understand something. Really understanding something, learning things from first principles will never limit your creativity. On the contrary, your creativity will flourish.

What limits us is to memorize dogma. Unfortunately, dogma is the bread and butter of many case interview resources. Laws and rules are set in stone and few candidates get to understand why they exist, let alone know when they should be broken.

Make sure you get onto that exponential curve!

Maybe people are telling you not to prepare too much because with current materials it’s worthless.

It’s like trying to learn calculus from an algebra book. Or to deeply understand math from a teacher that tells you all the rules but none of the explanations.

Under this hypothesis, “over preparation” is actually poor preparation: spending too much time with things that won’t help you.

I might be biased because I was super frustrated with the quality of the resources available to prepare to case interviews (which is why I chose to work with this and change this situation).

But I’ve heard from many candidates that they feel the same as well. If you too think this is the case, you are not alone.

Are McKinsey partners over prepared?

“Alright Bruno, there are many reasons why people might continue to spread the overpreparation myth even if it is false. But you still haven’t proved it is false. Maybe this is the one skill in which more preparation will make you worse at it…”

I love people who play devil’s advocate because they force you to be rigorous with your thinking.

I could go the easy way and tell you my personal story. The first time I applied I prepared a bit (i.e. I knew all the materials, had most of the casebooks and knew the lingo) and was considered “over prepared” by some. The second time I applied, I prepared A LOT (think 6 hours/day for four whole months) and no one thought I was over prepared.

People actually thought I was a natural, even though I was rejected by every firm just a year before. I got double offers and would’ve gotten more if I hadn’t stopped the recruiting processes of other firms. I know from personal experience that overpreparation is a myth.

But that would be anecdotal and perhaps it wouldn’t convince you.

I could tell you about the experience of our coaching clients.

None of our long-term clients have ever felt “over prepared”. They’ve all studied and practiced for countless hours and none ever felt robotic or that their creativity was stopping to flow.

I credit that to the fact that we’ve always made an effort to not give any rules and formulas they didn’t fully understand and could explain back to us. We have always put them into situations where those rules had to be broken so we knew they could apply the principles. Here’s what one client told us in a meeting we had with a group coaching group we taught, a couple of months after the coaching had ended:

What I was amazed by is the fact that in these past couple of months I have completely changed the way I think. Breaking down the problems and looking for the underlying logic in them is not something I have to try to do, it’s just something I do while I do stuff. And because I have learned this new way to think, I feel like I keep improving even though I am not practicing anymore. And I have been applying this to every area of my life”

I’ll be honest with you, these are not his exact words as we were having a couple of beers and it didn’t feel like the moment to take meticulous notes.

But that was the rough message and others on the table (who were on the same training) agreed with his opinion and shared their stories as well.

I wish I could take credit for what happened to them, but I won’t.

I had felt the exact same thing back when I was preparing and I had no coach to work with.

At one point, after months of struggle and frustration, everything fell into place. Instead of thinking hard during a case, I merely had to choose one of the structures and a few of the hypotheses that would pop up in my head. Then I communicated with the interviewer.

As I had internalized the thinking process, it started to happen less on my conscious brain and more on my unconscious.

It probably sounds odd to hear that, but you’ve been through a situation like this as well.

Learning to ride a bike or drive a car or play guitar are all very similar to this experience.

At first, it’s overwhelming: so many things to pay attention at once. So much thinking to do. It feels like juggling. At one point you internalize all of that and you just ride the bike, or just drive the car, or just play the guitar. There’s no thinking and worrying. Solving case interviews gets like that and I’ve seen many candidates achieving this level.

But if you’re the most skeptical person on earth you could argue that I’m a random internet guy and all these stories of thinking patterns changing are subjective bullshit.

To you, dear skeptic, I offer a final argument that comes from objective facts:

Do you think a McKinsey partner would be considered over prepared in a case interview?

You and I would agree he’d probably ace the case.

The case is a simulation of the real job, and here’s a guy who reached the top of the consulting field. You’d probably also agree that he’s got quite a bit of practice. Just think of how many projects, discussions and even case interviews he’s been through (although admittedly most on the interviewer side). No one’s practiced the way a consultant reasons through problems more than this person.

If you agree he wouldn’t “sound robotic”, or “force fit frameworks”, then there’s only one conclusion: over preparation is an illusion. The well-prepared person will always be better than the ill-prepared one (other factors held equal).

There may be a short-term dip in performance if you study until stage B and stop there, but if you just push a little further your performance will skyrocket by the time you reach stage C, the “confidence from competence” stage (or should I call it “case interview nirvana”?).

But as we’ve seen, if your teacher and materials aren’t good enough, more practice will only generate more frustration and make bad habits permanent. How to deal with that, then? How to get quality preparation instead of just doing more and more cases?

I’ll write another article on that, but for now, I’d love to get your comments on what do you think are essential elements in a preparation that has the necessary quality to reach stage C.

And as a next step for you to get some value out of this, two things for today.

First, try to assess in which preparation stage are you. Remember, Stage A folks tend to think they’re in Stage C, so make sure you’re not lying to yourself.

Second, based on the stage you’re in, try to plan your preparation a little bit. What are things you should be doing to get to Stage C as quickly as possible and go through less pain during Stage B? How are you going to make time for those things?